Patricia Girardi Shares the Magic of Plants, Bacteria, and Dinosaurs with Justice-Impacted Youth

I recently had the pleasure of attending a seminar given by Dr. Nalini Nadkarni, Professor Emeritus of Biology at the University of Utah. She spoke about her career-long mission to weave a tapestry grounded in ecology—one that tells stories of disturbance and recovery while crossing disciplines and communities. Part of this work culminated in the launch of the STEM Community Alliance Program (STEMCAP), which brings STEM programming to youth in custody and connects them with scientists, artists, and community educators. As a newly designated STEM Ambassador collaborating with STEMCAP, I was scheduled to present my research on plant–bacteria interactions to students at the Slate Canyon Youth Center (SCYC) just two days after her talk. These students are justice-impacted youth (aged ~14- 20) participating in an educational program designed to provide structure, support, and opportunities for growth during custody. Feeling a little starstruck, I asked Dr. Nadkarni if she had any last-minute advice. Her response was simple: humanize yourself. Show them that you are a person as well as a scientist.

With this advice in mind, I decided to start my workshop by discussing something very visible and personal: my tattoos. Although attitudes toward tattoos have evolved over time, they can still significantly influence how people are perceived. I wanted to show the students—many of whom have tattoos themselves—that having tattoos did not prevent me from pursuing a research career. I also used my lifelong fascination with dinosaurs, visually represented in my tattoos, to spark curiosity and lower the barrier to engaging with science. It worked! The students were immediately engaged by the stories behind my science-inspired tattoos, and the conversation helped establish rapport early.

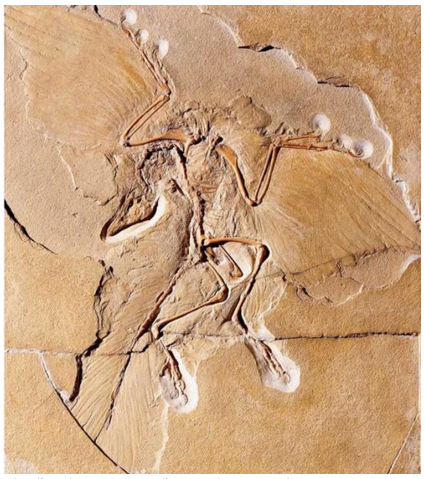

Left: Patricia's Arcaeopteryx tattoo. Right: The "Berlin specimen" was discovered in 1874.

I showed them an image of a famous Archaeopteryx fossil alongside my tattoo and asked them if they could guess which feature helped scientists link birds and dinosaurs. The answer: its beautifully preserved, feathered wings.

I continued to weave my lifelong fascination with dinosaurs into the story of how I became a PhD student. I wanted the students to understand that my path to research was anything but linear. As a college freshman majoring in English, I thought I’d left science behind. Through a series of unexpected pivots, I eventually found my way back to science. One turning point was taking GEO1040: World of Dinosaurs, taught by Mark Loewen, who was recently featured on Science Friday discussing a newly discovered ceratopsian—the skull of which I am standing beside here.

More important than any specific career milestone, however, was the message I wanted to leave with the students: I do not believe that being a scientist requires innate or exceptional talent. To me, being a scientist is the process of asking questions and making observations to answer them. The challenge lies in learning how to think logically—a skill that does not always come naturally but can absolutely be learned. Just as important is finding questions that matter enough that you are willing to spend time wrestling with them. Research does not have to be your original plan to become something meaningful and attainable.

The questions that interest me, and the ones I spent a lot of time engaging with

the students about, are those about how plants and bacteria interact and how we might

harness those interactions for human benefit—e.g., by borrowing the weapons bacteria

use against one another as alternatives to traditional antimicrobials. Translating

research for this audience of justice-impacted youth required a careful balance: I

wanted to provide enough context to justify my interest in these questions without

overwhelming the students with unnecessary technical details. I could not have done

this without the support of STEMCAP representatives Cenezhana, Jonny, and Nayra. Their

feedback helped me adapt my research content for this audience, brainstorm interactive

components, and refine my presentation as part of my preparation for the workshop.

The questions that interest me, and the ones I spent a lot of time engaging with

the students about, are those about how plants and bacteria interact and how we might

harness those interactions for human benefit—e.g., by borrowing the weapons bacteria

use against one another as alternatives to traditional antimicrobials. Translating

research for this audience of justice-impacted youth required a careful balance: I

wanted to provide enough context to justify my interest in these questions without

overwhelming the students with unnecessary technical details. I could not have done

this without the support of STEMCAP representatives Cenezhana, Jonny, and Nayra. Their

feedback helped me adapt my research content for this audience, brainstorm interactive

components, and refine my presentation as part of my preparation for the workshop.

I am so grateful to the students and staff at SCYC for welcoming me into their space and for their participation in the workshop. The response from the students was deeply humbling. Several approached me afterward to shake my hand, thank me for coming, or introduce themselves—small gestures that carried enormous weight. Their responses during the workshop and afterward affirmed that being open, honest, and relatable mattered. This experience reinforced my belief that representation, vulnerability, and curiosity are powerful tools in science communication. If even one student walked away feeling that research—or curiosity itself—is something they are allowed to claim, then the workshop succeeded. I left Slate Canyon Youth Center reminded that science is not just about experiments and data, but about people, stories, and the many paths that lead us to ask questions about the world.

About the Blog

Discussion channel for insightful chat about our events, news, and activities.

Categories

Featured Posts

Tag Cloud

- STEMCAP (1)

- tattoos (1)

- dinosaurs (1)

- microscopy (1)

- conservation (2)

- education (1)

- Puerto Rico (2)

- bilingual (1)

- UoG (2)

- Guam (2)

- ethnobotany (1)

- environmental policy (1)

- student immersion (1)

- engineering (1)

- Virgin Islands (1)

- USVI (2)

- lionfish (1)

- children's home (1)

- marine ecology (1)

- youth (1)

- sustainability (2)

- Utah (1)

- Arizona (1)

- Nevada (1)

- southwest (1)

- virtual (1)

- project management (1)

- training (1)

- naturalist (1)

- forest (1)

- ecosystem (1)

- Spanish (1)

- library (1)

- Huntington's (1)

- medical science (1)

- Emmanuel Ngwoke (1)